There are no items in your cart

Add More

Add More

| Item Details | Price | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Read the passage and answer the following questions

In the animal kingdom, mimics are a dime a dozen. Stick insects pretend to be twigs. Hawk-moth caterpillars resemble venomous snakes. Edible heliconid butterflies disguise themselves with the wing patterns of noxious ones, and noxious ones copy each other to make it easier for predators to learn what not to eat. All these examples, though, are visual. Auditory mimicry is rarer. But, as he describes in Current Biology, Danilo Russo of the University of Naples Federico II thinks he has found a novel case of it. Some bats, he believes, mimic angry bees, wasps and hornets in order to scare away owls that might otherwise eat them. Dr Russo first noticed the propensity of greater mouse-eared bats to buzz a few years ago, when he was collecting them...to study their ecology. The noise struck him as similar to the sound of hornets that inhabited the area of southern Italy he was working in. That led him to wonder whether bat buzzing was a form of mimicry which helped its practitioners to scare off would-be predators. To test this idea, he... and a colleague...first recorded the buzzing that captured bats made when handled. Then, having donned suitable protective clothing, they embarked on the more dangerous task of recording the buzzing made, en masse, by four different species of Hymenoptera: European paper wasps; buff-tailed bumblebees; European hornets; and domestic honeybees.... For the next part of their experiment Dr Russo and Dr Ancillotto recruited the services of 16 captive owls-eight barn and eight tawny. Both of these species are known to hunt bats. The researchers put the owls, one at a time, in an enclosure equipped with branches for them to perch on, and also two boxes with holes in them. The boxes resembled the sorts of cavities in trees that owls would explore in the wild for food. They placed a loudspeaker alongside one of the boxes and, after the birds had settled in, broadcast through it five seconds of uninterrupted bat buzzing and a similar amount of insect buzzing three times in a row for each noise. As a control, they broadcast in like manner several non-buzzing sounds made by bats. During the broadcasts (which occurred in random order) and for five minutes thereafter, they videoed the owls. The videos were then analysed, by an independent observer, without benefit of their soundtracks. The results were unequivocal. When they heard both the bat buzzings and the hornet buzzings the owls moved as far from the speakers as they could manage. In contrast, when the non-buzzing bat sounds were played, they crept closer. Dr Russo and Dr Ancillotto believe this is the first reported case of a mammal using acoustic mimicry to scare away a predator. They strongly suspect, however, that it is not unique. Anecdotes suggest several birds and also small mammals, such as dormice-particularly species that dwell in trees and, like dormice, in rock cavities-make buzzing noises when their hidey-holes are disturbed. This has not yet been documented formally as acoustic mimicry. But, given the propensity for venomous buzzing insects to dwell in those sorts of places too, and also the fear that these insects generate in other species, human beings included, Dr Russo thinks this may well be what is going on. He therefore predicts that when these other buzzes are recorded and analysed the results will show that acoustic mimicry by vertebrates of stinging insects is far more widespread than currently realised.

Read the passage and answer the following questions

Familiar though his name may be to us, the storyteller in his living immediacy is by no means a present force. He has already become something remote from us and something that is getting even more distant. To present someone like Leskov as a storyteller does not mean bringing him closer to us but, rather, increasing our distance from him. Viewed from a certain distance, the great, simple outlines which define the storyteller stand out in him, or rather, they become visible in him, just as in a rock a human head or an animal's body may appear to an observer at the proper distance and angle of vision. This distance and this angle of vision are prescribed for us by an experience which we may have almost every day. It teaches us that the art of storytelling is coming to an end. Less and less frequently do we encounter people with the ability to tell a tale properly. More and more often there is embarrassment all around when the wish to hear a story is expressed. It is as if something that seemed inalienable to us, the securest among our possessions, were taken from us: the ability to exchange experiences. The earliest symptom of a process whose end is the decline of storytelling is the rise of the novel at the beginning of modern times. What distinguishes the novel from the story (and from the epic in the narrower sense) is its essential dependence on the book. The dissemination of the novel became possible only with the invention of printing. What can be handed on orally, the wealth of the epic, is of a different kind from what constitutes the stock in trade of the novel. What differentiates the novel from all other forms of prose literature -the fairy tale, the legend, even the novella-is that it neither comes from oral tradition nor goes into it. This distinguishes it from storytelling in particular. The storyteller takes what he tells from experience-his own or that reported by others. And he in turn makes it the experience of those who are listening to his tale. The novelist has isolated himself. The birthplace of the novel is the solitary individual, who is no longer able to express himself by giving examples of his most important concerns, is himself uncounseled, and cannot counsel others. To write a novel means to carry the incommensurable to extremes in the representation of human life. In the midst of life's fullness, and through the representation of this fullness, the novel gives evidence of the profound perplexity of the living. Even the first great book of the genre, Don Quixote, teaches how the spiritual greatness, the boldness, the helpfulness of one of the noblest of men, Don Quixote, are completely devoid of counsel and do not contain the slightest scintilla of wisdom. If now and then, in the course of the centuries, efforts have been made-most effectively, perhaps, in Wilhelm Meisters Wanderjahre-to implant instruction in the novel, these attempts have always amounted to a modification of the novel form. The Bildungsroman, on the other hand, does not deviate in any way from the basic structure of the novel. By integrating the social process with the development of a person, it bestows the most frangible justification on the order determining it. The legitimacy it provides stands in direct opposition to reality. Particularly in the Bildungsroman, it is this inadequacy that is actualized.

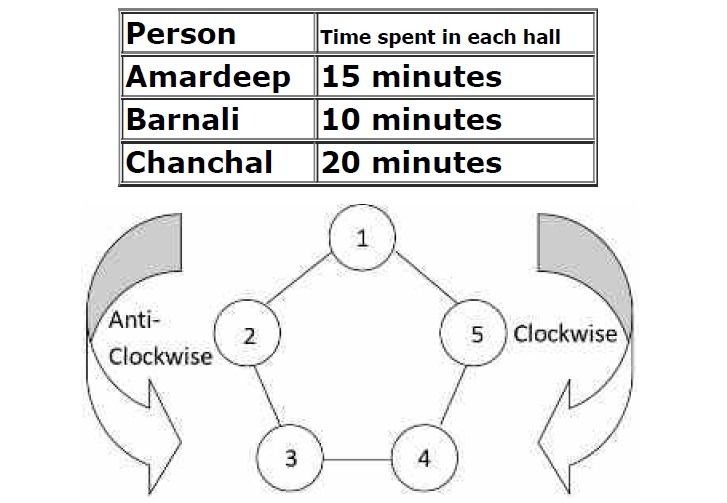

A museum has five halls. Each hall has a separate entry ticket which must be purchased right before entering that hall. The ticket price for each hall is non-zero and unique. Moreover, the ticket price for each hall is a multiple of 30. Hall-3 and Hall-1 have the maximum and minimum ticket prices, respectively. Ticket price of Hall-5 is twice that of Hall-4. A visitor must visit Hall-1 first before deciding the sequence (clockwise, i.e. 1->5->4->3->2 OR anti-clockwise, i.e. 1->2->3->4->5) of visiting the remaining halls. Three photographers - Amardeep, Barnali, and Chanchal, visited all the halls by purchasing tickets worth Rs 450 each. Moving from one hall to another took five minutes for each of them. Table 1 below provides the time spent by the three photographers in each hall. Visiting a hall is considered complete only after a photographer spends the specified time (as given in Table 1) in that hall. Consider the time taken to purchase the ticket as negligible. The floor plan of the museum is given in Fig. 1 (each circle represents a hall, e.g. circle numbered 1 represents Hall-1).

The following additional information is given:

1. Barnali's sequence of visiting the halls was different from Amardeep's and Chanchal's.

2. Chanchal entered Hall-1 at 10:08 Hrs. She spent Rs 120 by 10:40 Hrs.

3. Amardeep left Hall-2 two minutes after Chanchal entered that hall. Amardeep entered Hall-5 five minutes after Barnali entered that hall.

Let’s assume ticket prices:

By 11:35 Hrs, Barnali visited three halls: Hall-1, Hall-2, and Hall-4.

Total spent = ₹30 + ₹60 + ₹90 = ₹210

Correct Answer: D (₹210)

Calculating the time for each hall:

Chanchal completes all halls by 12:08 Hrs.

Correct Answer: B (12:08 Hrs)

Logic:

Correct Answer: D (Hall-4)

Conclusion: By 12:00 Hrs, only one photographer (Amardeep) had completed all halls.

Correct Answer: C

Conclusion: The last photographer to complete Hall-3 was Barnali at 11:55 Hrs.

Correct Answer: B

Case 1: Both

Two parabolas can intersect at most at two points. Therefore, out of the

Case 2: One of

A straight line and a parabola can intersect at most at two points. By similar reasoning, the set

Case 3: Both

Two distinct straight lines intersect at exactly one point. Therefore, the set

Hence, in all cases, the number of distinct elements in the set

Correct Answer: A

Total cases: The total number of arrangements of 22 balls, including 10 red and 12 blue, is:

Favorable cases: The number of arrangements where the last ball is red can be calculated by treating the last red ball as fixed and arranging the remaining 21 balls (9 red and 12 blue):

Probability:

Correct Answer: A

Q16. Who was the last photographer to complete visiting Hall-3, and at what time did the last photographer complete visiting Hall-3?

Q16. Who was the last photographer to complete visiting Hall-3, and at what time did the last photographer complete visiting Hall-3?